ONDC Explained

no....really

I am not an expert on ONDC; I have read all news stories published about it and talked to two people who are involved with the project - one a senior leader in the firm and another who interned with the organization and is also in the early stages of operating a business through the network. I will now try to explain what it is and isn't, some of the nuances, a little bit about the technology behind it, the economic logic, and the private and public figures and institutions making this happen. In attempting to explain ONDC, I hope I will be forced to examine gaps in the mental model I have built. I will also try to touch on platform businesses, the incentive structures that govern them, and why ONDC may disrupt them.

(I will try not to mention UPI in this article because while there may be some similarities in how the projects came up and it serves as a good indication of the scale and impact ONDC wants to achieve, it is not a helpful analogy in building an understanding of ONDC. This is because (1) I don't fully understand how UPI works, and more likely than not, neither do you; therefore we may mistakenly apply our poorly built frames around UPI to ONDC; (2) there is a loss of nuance inherent in such comparisons and analogies, which is against the aim of this exercise)

We will center our analysis on retail e-commerce because that is the most intuitive, and we would also be able to put ourselves in the shoes of the various service providers involved in the business. By the end, hopefully, you will be able to imagine how ONDC can work for other applications.

Here's what we will cover:

Platform businesses and the current digital commerce landscape in India

What is ONDC and what it isn't

History of ONDC, formation and some technical stuff

Platform businesses

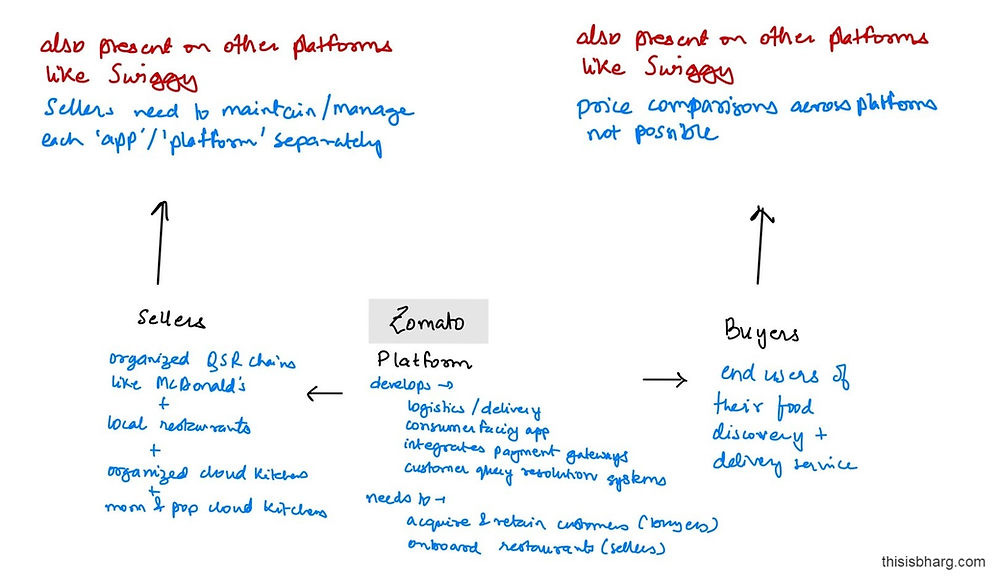

Platform businesses like Zomato have multiple jobs to do - they have to onboard restaurants (sellers), and also have to acquire consumers (buyers). A critical mass of both is required before the platform becomes viable. Customers will stop using the app if they don't find enough variety of food options, and restaurants won't want to try registering on an app and maintaining a separate workflow if they don't get enough incremental customers. The charges (platform fees) for the increased visibility that a restaurant receives and the delivery services have to be lower than what monies incurred would be if the restaurant were to set up its own delivery systems. Similarly, the added convenience for the end user has to be worth the delivery fees that they incur, or else they would directly order from the restaurant or go pick up their order or eat out.

Solving for both the buyer and seller sides requires extraordinary investments, thus erecting very high barriers to entry. Eventually, as the market becomes dominated by a few platforms, each can exercise more power - i.e., throw their weight around and dictate terms for both sellers and buyers. The platform knows that both buyers and sellers both have very few options. Also, all platform players become stores of values independent from each other (they operate in siloes - another metaphor most loved by MBA types like me), i.e., they are unable to (and are disincentivized to) exchange information. Another implication of this silo-ing is that a buyer and a seller can interact only if both are on the same platform (foreshadowing for later).

The concentration of relative power in the ecosystem also leads to a few points of failure. The classic, all eggs in one basket threat emerges for sellers, who might have become dependent on a single platform for a large chunk of their business. These platforms can also act as gatekeepers and may enact policies that prefer certain participants over others, with no incentives or control mechanisms forcing them to be transparent. Sellers are also locked in and suffer from what is known as the portability of trust problem. If a restaurant on Zomato realizes they have a large, consistent demand base in their area and want to start delivering on their own, they will run into a few problems. While it makes sense that the restaurant doesn't want to pay the platform fees and retain that value for themselves, they may soon realize that it may be almost impossible:

Convincing people to stop using a perfectly fine app may be very difficult

The users also trust Zomato to take care of any issues with payments, issues with deliveries, etc

Platforms to network

A lot of bottlenecks (in addition to the ones discussed above) exist in platform businesses. And we haven't talked about category-specific problems that might exist in other types of digital commerce. These problems are only compounded by India's sheer diversity and size and the fact that the digital commerce ecosystem is nascent. While many private participants are trying to solve these problems, with the most recent thrust aimed at increasing digital adoption among small sellers (see Jio Mart); a coordinated strategy that operates at the scale of the entire country might help.

A paradigm shift from scaling what works to identifying what works at scale

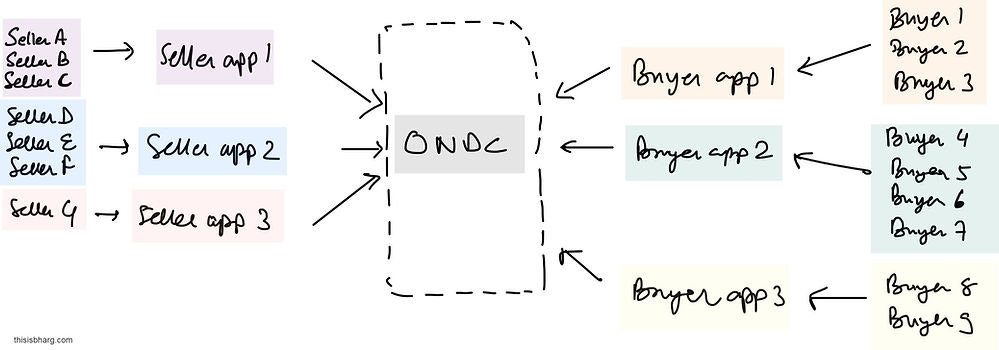

An approach that unbundles this chain can enable greater participation and if this system is built on a decentralized network that allows interoperability (buyers and sellers don't have to be on the same platform) and aligns incentives such that the success of the network (and all participants) is predicated on the success of the end users, can be truly revolutionary.

But wait, let's see how this looks visually; some things might become clearer.

Participants on this network, unlike platforms only have to solve for one side of the equation. Seller apps worry about onboarding and helping sellers while buyer apps worry about serving the end customer. If you are a restaurant on Zomato, only those end users using Zomato will be able to discover you. But with ONDC, being present on just one seller app makes you visible to all buyers on all the buyer apps.

Also, all those videos you see on YouTube about ordering food via ONDC? Well ... they are not quite accurate. You can't order via ONDC, you can only order via a buyer app on the ONDC network. And because ONDC has a lot of buzz right now, some apps use the ONDC label, but there is no real reason why an end-consumer ever has to know that the app they use is on the network.

Now, who are these buyer apps or these seller apps? Any player who has acquired a customer base and wants to engage in some commercial activity can add a digital commerce functionality or develop a buyer app. For example, PhonePe, the country's number one UPI payments application, has deep expertise in app design and managing payment transactions. This is why they launched a hyper-local delivery buyer app called Pincode, which offers seamless login and payments through PhonePe and all other digital payment methods. But unlike Dunzo, Zepto, or any other q-commerce players, Pincode didn't have to build dark stores or onboard local Kirana stores. They just had to build the buyer-facing app. Whatever you read on the internet might seem confusing because there are players like magicpin who operate on the buyer side and seller side.

At the risk of ordering khayali pulao from Pincode, let me lay down what the future might look like. A business management platform like Khatabook has many small businesses registered with it that might be selling their products/services to an end consumer in some fashion - say kirana stores; can come onto the ONDC network, allowing for all customers of Khatabook to become sellers. This can be done through the Khatabook app or they might wish to create a separate Khatabook Commerce application. That is to say, any business/service/participant who by some means has accumulated enough potential online sellers can plug into the ONDC network and enable sellers to start selling online. In a pre-ONDC world, if Khatabook had digital commerce ambitions, it would have had to build an app (platform) and acquire customers for that app, which would compete with the likes of Blinkit.

Similarly, any service that has onboarded/acquired enough consumers, can plug into the ONDC network. For example, Google Maps has a lot of people looking for directions. Presumably, by plugging into ONDC, users of Google Maps can get a list of sellers of mobility services. This is achieved on the backend by multiple aggregators of mobility services (seller apps) who are also present on the ONDC network. This obviates the need for Google to create an app (platform) for rickshaw drivers or taxi drivers to register.

The above two examples hopefully also get you excited for the future.

Now let me blow your mind even further: have you heard of how restaurants might have to figure out deliveries themselves with ONDC? Well, that's not true. Let's go back to PhonePe/Pincode. They don't have expertise in logistics and managing a fleet of gig workers! But Amazon does, and so does Delhivery. Well if these logistics experts plug into ONDC, they can provide their services to buyer apps. The diagram will look something like this -

ONDC enables multi-pronged interactions

In fact, this is exactly what Amazon has committed to do, in addition to providing their store management and retail digitization services (SmartCommerce) via ONDC.

One more thing: if a restaurant (seller) wishes to switch seller apps (for whatever reason), their reputation will be ported to the other seller app. The network enables this portability, and no lock-in is created, unlike platforms.

Now, you may ask, how is the seller matched with a buyer? Will some service providers be preferred over others? We will handle all of that in the next part of this piece. But first, let's rewind and get some facts straight.

History and technical stuff

We will have to roll all the way back to NASSCOM - the National Association of Software and Service Companies, which is a non-governmental trade association - an industry body and an advocacy group that works closely with the Indian government.

Then came iSPIRIT - Indian Software Products Industry Round Table - a think tank, which started as a NASSCOM offshoot. They are involved in, among other things, promoting the India Stack, a highly ambitious project involving Aadhar, eKYC, eSign, UPI, and DigiLocker, and many other things I am forgetting.

Then came Beckn Foundation who in partnership with iSPIRIT developed the Beckn Protocol. And just by the way, the brand "Beckn" is owned by Open Shared Mobility Foundation, whose sole investor is Nandan Nilekani. And yes, Mr. Nilekani is involved in all of the projects and organizations I have listed above.

So what is the Beckn protocol? Well - it is the set of rules that enable the interoperability. It is the "open" of it all!! It contains a lot of specifications for building networks that enable/facilitate e-commerce. So Beckn is the protocol - the HTTP (from the internet world) equivalent in commerce, and ONDC is an adaptation of the protocol.

ONDC is a private non-profit Section 8 company. The Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade (DPIIT) set up a nine-member advisory council in July 2021. It tasked the QCI* to incubate ONDC. Between November 2022 and March 2023, various banks - public and private - like PNB, Kotak Mahindra, SBI, etc, and various organizations like CDS, SIDBI, NSE, and the similarly complicated NPCI all picked up stakes by contributing seed money.

Quality Council of India, which is an autonomous body set up by the Ministry of Commerce and Industry, and various industry associations like ASSOCHAM, CII, FICCI who became promoters

Now, some of the clarifications I had promised earlier - ranking and discovery specifications are required to be made available to all participants. No black boxes can exist.

Charges? Well it's a bit complicated - usage charges may be rolled out soon - but this is like UPI again ... who is paying for all the tech and the infrastructure, I don't know! Charges for the buyer and seller apps - you can read about that on the excellent FAQ page.

How are the big e-commerce players responding to ONDC? Some are dipping a toe in the river, like Amazon who I mentioned plans to offer their logistics services through the network; most it would seem are waiting and watching.

Details like grievance redressal, weeding out bad actors, and exact details on the liability of network participants are being worked out.

How to deal with large players that operate on both the seller and buyer side who may tip the system in their favor? Piyush Goyal and the likes are hoping that the entrenched players like Paytm, Zomato etc. come onto the network fully, and not create offshoots.

But this is an evolving space and things will change (hopefully for the better).

It is envisioned that all ONDC will need to do in the future is maintain the set of APIs that enable buyer and seller apps to plug into the network. Sounds awesome right?

Reading List:

https://docs.setu.co/commerce/ondc/overview

https://community.nasscom.in/communities/application/what-beckn-protocol-backbone-ondc

https://developers.becknprotocol.io/docs/introduction/introduction/

https://www.medianama.com/2022/09/223-ondc-commissions-grievances-search-rankings-ratings/

Nice, concise explanation of ONDC. Thank you!

Detailed explanation and interesting articulation!